Why Embracing Lifelong Learning as a Leader Results in Greatness for your Organisation (or Empire)

What do Baghdad, Cordoba and the top tech companies have in common and what can we learn from them?

What do Baghdad, Cordoba and the top tech companies have in common and what can we learn from them?

“The fish rots from the head down.” — Turkish proverb

This phrase is quite commonly used today in business circles to denote that a problem within the organisation is most likely the cause of bad leadership, or when a company fails, the leadership is the root cause.

What then, if the situation was reversed? Is the inverse also true? If a society or organisation is successful, does that mean it’s solely due to excellent leadership? Or are there other factors at play?

Anthony Robbins, the indomitable self-help guru is known to say ‘success leaves clues’ — and through ‘modelling’ those who have achieved what you’d like to achieve, you can get to your destination quicker.

With this in mind, I wanted to look at some examples in history that are often revered and looked upon as a shining example of an era of peace and prosperity, and take a look at the factors that led to it being considered a golden age of civilisation — and if there’s anything we can learn to apply, today.

Looking to the Golden Age of Islam for inspiration

In the Islamic world, we know there was a time, of course when Muslims WERE pioneers, they were advanced and not only led but changed the world with their innovation, drive and impact.

We all know the story. We look back with pride, and perhaps tinged with some sadness that we are far from that reality today.

There are two cities in particular that immediately come to mind when one thinks of the Islamic golden age. These two cities, these two hubs of learning were the epicentres of this massive intellectual revolution.

One in the East, and one in the West.

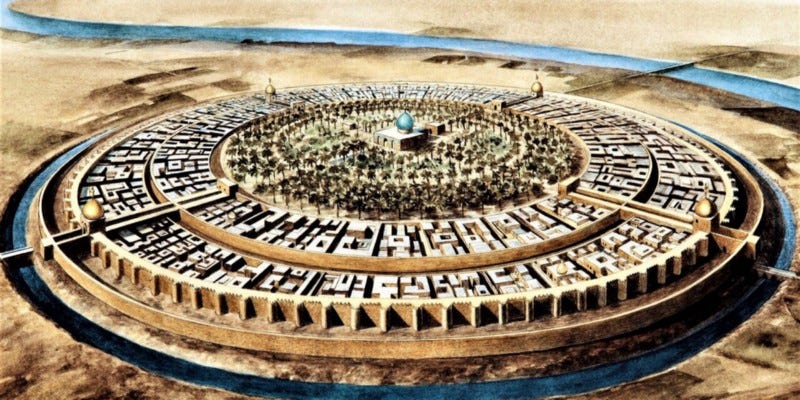

In the East, was Baghdad. The home of the infamous House of Wisdom.

In the West, was Cordoba, in Al-Andalus, known at the time as “the Ornament of the World.

Both had world class libraries and educational institutions and produced some of the leading thinkers and scholars of all time. Both hubs pioneered inventors and innovators who went on to discover things that we still benefit from, today — some 800–1000 years later.

Some of the biggest achievements that advanced science from al-Andalus include major advances in trigonometry (Jabir ibn Hayyan), astronomy (ar-Zarqali), surgery (Al Zahrawi), and pharmacology (Ibn Suhr) amongst many others. For Baghdad, algorithms and algebra (Al-Khwarizmi), optics, geometry and the scientific method (Ibn al Haytham) and all sorts of advances in medicine (Ibn Sina) to name but a small few.

They were rivals, but working towards the same vision — to please God and for Islam to benefit and impact the world.

9th century geographer and historian Al Ya’qubi described the early Baghdad as a city ‘with no equal on earth, either in the Orient or the Occident,’ being ‘the most expensive city in area, in importance, in prosperity,’ and that ‘no one is better educated than their scholars.’

In David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years (2014) it was said:

“At its height, during the eighth and ninth centuries, the Baghdad-based Abbasid caliphate was the richest and largest empire the world had ever seen in terms of per capita wealth.”

Victor Robinson in The Story of Medicine (1932) wrote of 10th Century Cordoba;

“Europe was darkened at sunset, Cordoba shone with public lamps; Europe was dirty, Cordoba built a thousand baths; Europe was covered with vermine, Cordoba changed its undergarments daily; Europe lay in mud, Cordobas streets were paved; Europe’s palaces had smoke-holes in the ceiling, Cordobas arabesques were exquisite; Europe’s nobility could not sign its name, Cordoba’s children went to school; Europe’s monks could not read the baptismal service, Cordoba’s teachers created a library of Alexandrian dimensions.”

High praise indeed.

So, what was their secret?

An authentic zeal and genuine passion for knowledge and reading — from the very top

If we study the two periods more closely, there are lots of similarities you notice.

Let’s start with the jewel of Europe, Cordoba, circa 10th Century. The city was 24 miles long and 10 miles wide. It’s population was one million. There were 380 mosques, 800 madrasahs and numerous personal and 70 public libraries.

But what stood Cordoba apart from any of her rivals, was their fervent approach and attitude towards seeking knowledge. They absolutely devoured it. And this was very much a top-down approach — an attitude set by the leadership themselves.

Take Al-Hakam II, the Caliph of Cordoba in Al-Andalus (r. 961–976), for example. The best teachers of al-Andalus had educated al-Hakam, and thanks to that education he grew up to become a cultivated prince, a lover of culture and good literature. As such, he was extremely fond of books and ongoing learning (which may just be an understatement!).

It is said that he amassed a vast library that contained at least 400,000 books (and some sources say 600,000), spanning disciplines as diverse as philosophy, religion, literature, science, mathematics, astronomy, meteorology, alchemy, geometry, architecture, medicine, and more. Just the catalogue of his Royal Library alone consisted of forty-four volumes! The library itself was so big that it gave employment to over 500 people and soon outgrew its palace location to command its own purpose built building, a few miles away.

What is even more staggering is that al-Hakam II allegedly read and commented in the margins of every single one of the books in the Royal Library! This claim may be hyperbolic and perhaps intended to add to his legend, but it shows the extent to which Caliph al-Hakam II loved books and reading himself. It was a genuine passion — not just something he encouraged for political or economic reasons. Moreover, al-Hakam II dispatched book hunters to Baghdad, Cairo, Damascus, Constantinople, Basra, and other knowledge centers in search of the rarest books. He preferred to stockpile books rather than arms, and books were the best gifts with which other kings could buy his friendship.

Due to this mindset, Cordoba fast became the centre of learning and intellectual life in the world, and was widely known as a city of bibliophiles; people who love books.

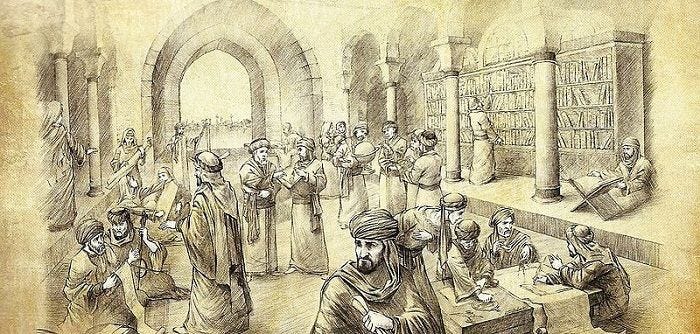

Looking now at Baghdad, it was a city inhabited that between 800,000 to over 1.5m people, depending on which source. By way of comparison, both London and Paris had a population of circa 20,000 at the time. It was the most advanced metropolis of its time, by far.

Their leadership loved knowledge. The infamous Bayt ul Hikma (also known as the House of Wisdom) was founded by Caliph Harun al-Rashid (r.786–809) and came to further fruition under his son Caliph al-Mamun (r 813–833), who is credited with its formal institution. The library they built was also one with over 400,000 books — the most in the world at the time. We can compare this to the largest libraries in Western Europe that had only hundreds of books. Even into the 14th century, the library at the University of Paris only had about 2,000 books (McClellan & Dorn, 1999).

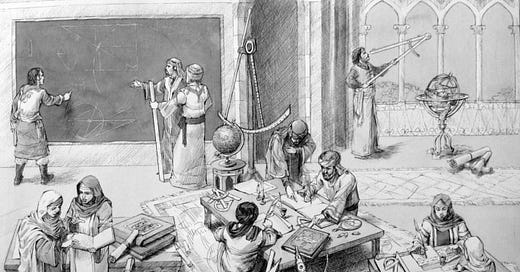

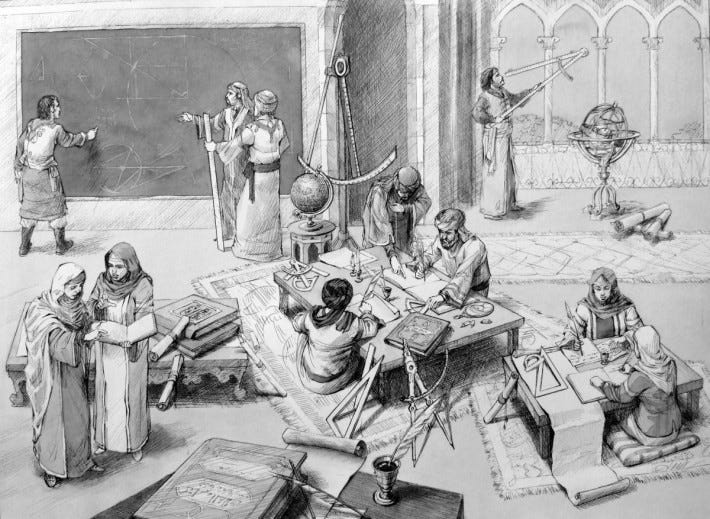

They provided all necessary resources and support for initiating the House of Wisdom project and a safe and sound environment that brought thinkers, men of knowledge from near and far to the capital. They personally supervised the collection of manuscripts from around the world, written in Greek, Latin, and Persian in the fields of medicine, alchemy, physics, mathematics, astrology and other disciplines. The rulers not only supported the project but also took part in discussions and debates among the intelligentsia which displayed their personal interest.

Knowledge Seeking Becomes the Status Quo

Back in Cordoba, the cultivated Caliph’s love for books and reading ultimately made his city the centre of learning for the world. This love for books trickled down to his people. It fast became a status symbol.

Aristocrats and scholars imitated the caliph by founding their own private libraries, and thanks to the economic and cultural levels of development of al-Andalus of this period, private libraries flourished in Al-Andalus. The prestige of the royal library led to a spirit of competition between the viziers, deputies, each wishing to attract scholars and rarest library talents.

“Andalusia was, above all, famous as a land of scholars, libraries, book lovers and collectors…in Cordoba books were more eagerly sought than beautiful concubines or jewels…the city’s glory was the Great Library established by al-Hakam II…” Richard Erdoes, 1000AD Berkley, Seastone 1998, pp60–61

The people of Cordoba also collected books for their homes. Those who owned personal libraries were regarded as important figures in Cordoban society. It was said that Cordoba was the greatest book market in the western world in the 10th century” (Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World 4th ed [1999] 81).

According to Ibn Said, “Córdoba held more books than any other city in al-Andalus, and its inhabitants were the most enthusiastic in caring for their libraries.”

Dutch Arabic scholar Rheinhart Dozy (1883) wrote that every person in Islamic Spain could read and write, while in Europe only priests and some aristocrats knew how to read and write.

S.P Scott writes in “The History of the Moorish Empire in Europe” that:

“There were knowledge and learning everywhere except in Catholic Europe. At a time when even kings could not read or write, a Moorish king had a private library of 600,000 books. At a time when 99 percent of the Christian people were wholly illiterate, the Moorish city of Cordoba had 800 public schools, and there was not a village within the limits of the empire where the blessings of education could not be enjoyed by the children of the most indigent peasant . . . and it was difficult to encounter even a Moorish peasant who could not read and write.”

Bayt-ul-Hikma was to Baghdad what Al Hakam’s Royal Library was to Cordoba. It consisted of a library, translation bureau, observatories, reading rooms, living quarters for scientists & administration buildings. More than anything, it was a research and educational centre where leading scholars from various fields came to share their knowledge. The House of Wisdom was the largest repository of books in the whole world already by the middle of the ninth century. It was the leading centre for the study of mathematics, astronomy, medicine, alchemy, chemistry, zoology, geography and cartography — and the impact on society was revolutionary.

Facilitating Learning and creating a knowledge seeking culture of the highest standard

None of this happened by accident. It was by design.

What really fostered the spirit of research and knowledge-seeking in Cordoba were the extremely supportive measures taken by the Caliph al-Hakam II to bolster education and learning in his kingdom.

It was engineered into the very fabric of his society.

Writers, translators, and book-makers were exempt from participation in wars and conquests. They were also given precious gifts in return for their work and provided with excellent working conditions.

He encouraged writing and authorship, and would often send writers generous gifts for their books. A famous story recalls he once sent 1,000 Dinars of pure gold to an author in Isfahan, for a copy of his new book. By way of comparison, a year’s salary at that time was 240 dinars. Later, books written all the way in Persia were dedicated to the Andalusian Caliph.

The massive efforts undertaken by the Caliph to promote education, learning, and science in Cordoba contributed to the flourishing of the Arabic language which soon became known as the language of the learned.

Scholars, researchers, and students from all over Europe then headed to Cordoba to learn this rich language which provided them with ample learning and job opportunities.

It was the same in Baghdad.

The Islamic Empire in Baghdad heavily patronized scholars. The money spent on the Translation Movement in the House of Wisdom for some translations was estimated to be equivalent to about twice the annual research budget of the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council. The best scholars and notable translators, such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq, had salaries that are estimated to be the equivalent of the top professional athletes today.

Every scholar’s dream, Muslim or non-Muslim, was to join Baghdad to be part of al-Ma’mun’s project, especially with the very generous treatment of translators by the Caliph. It was said that if a scholar translated any book from its original language into Arabic, he would be given that book’s weight in gold. Thus, translators and scholars from all faiths and regions flocked to Baghdad, to translate work from Ancient Mesopotamia, Rome, China, India, Persia, Egypt, Greece and Byzantine civilizations.

Women had an important role to play

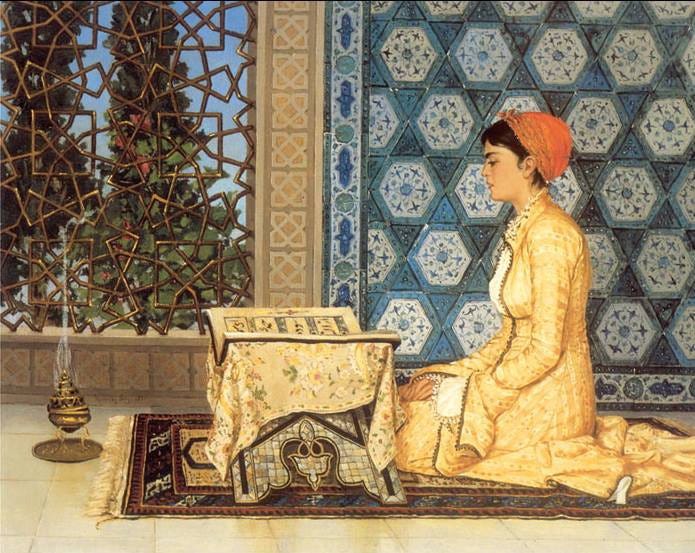

Lubna of Cordoba was director of the famous Cordoba library and she was responsible to reproduce, write and translate new volumes. She was also the palace secretary of Caliph Abd al-Rahman III (al-Hakam’s father) as well as during al-Hakam’s reign. According to Arab chronicles at the time of al-Hakam II, in some areas of Cordoba, there were more than 170 female library clerks, carefully hand-copying books, while calligraphers and bookbinders created beautiful text and cover designs. Library clerks, many of them women, which not only gives the idea of culture, but also the place of women in the reign of the enlightened Caliph.

In Baghdad, Zubayda bint Jaf’ar, the wife of Caliph Harun al-Rashid was influential in the movement. She spent lavishly from the Caliphal purse on public works, including repairing the well of Zamzam and she also financed one of the greatest public-works projects of the era: the construction of a 1,500km road (now named after her) from Kufa, south of Baghdad, all the way to Makkah. She even was instrumental in making the right decision when choosing her stepson, Mam’un to be the next Caliph over her own son, who she feared had been corrupted. Al-Mamun continued the excellent work of his father, and brought many well-known scholars to Baghdad to share information, ideas, and culture in the House of Wisdom.

They encouraged polymathy and holistic learning

In addition, in this era, the scholars acknowledged the religion of Islam confirmed the unity of all knowledge, so they sought out its sources and encouraged it. So the early scholars of Islam were all polymaths — they linked maths, art, law, philosophy and other sciences togeteher with Islam. The House of Wisdom, for example, was much more than an academic centre removed from the broader society. Its experts served several functions in Baghdad. Scholars from the Bayt al-Hikma usually doubled as engineers and architects in major construction projects, kept accurate official calendars, and were public servants. They were also frequently medics and consultants.

“Muslim theologians demonstrated an intellectual versatility beyond any other group. The likes of Al-Ghazali, Al-Razi and Al-Tusi were scholars of religion as much as they were physicians, poets and philosophers. The polymathic culture was so embedded in the Islamic world that even Christian and Jewish polymaths such as Maimonides, Hunayn ibn Ishaq and Abraham ibn Ezra thrived under it.” The Polymath, Waqas Ahmed

They, as most Islamic thinkers of the time, saw all knowledge as something to pursue as the more knowledge one has, the more they can get to know their Lord.

“Up until recent times, Islamic thought was characterized by a tendency toward unity, harmony, integration, and synthesis. The great Muslim thinkers were masters of many disciplines, but they looked upon them as branches of the single tree of ‘Tawhid’. There was never any contradiction between astronomy and zoology, or physics and ethics, or mathematics and law, or mysticism and logic. Everything was governed by the same principles, because everything fell under God’s all-encompassing reality.” — William Chittick

Ongoing Investment in Learning and Development

By the 10th century, we have established the city of Cordoba was already a paradise for scholars, translators, philosophers, and intellectuals of all disciplines who flocked there in great numbers and made it Europe’s intellectual hub. It didn’t just stop there.

In addition to the many libraries and collections, al-Hakam II provided for at least twenty-seven free schools for the poor. He also provided academies and financially provided for the University of Córdoba. One of its most famous buildings was the Cordoba Mosque. This building housed the largest university in Europe at the time with over four thousand students.

There were then further universities developed in major cities Cordoba, Seville, Toledo and Granada equipped with vast libraries.

In the Dar al-Kitabat there was a flock of scribes engaged in copying books, and an equal number of bookbinders. A librarian was given a very handsome salary. There was a market where only books were sold.

Under the sponsorship of caliph Al-Ma’mun, economic support of the House of Wisdom and scholarship in general was greatly increased. It was easy for scholars and translators to make a living and an academic life was a symbol of status; scientific knowledge was considered so valuable that books and ancient texts were sometimes preferred as war booty rather than riches.

Al-Ma’mun was also the first ruler to fund and monitor the progress of major research projects involving a team of scholars and scientists.

Open-mindedness and a willingness to learn from others

We should not be ashamed to acknowledge truth from whatever source it comes to us, even if it is brought to us by former generations and foreign peoples. For him who seeks the truth there is nothing of higher value than truth itself. — Al-Kindi

The library of al-Hakam II included books of the Hispano-Gothic tradition, learning from Ancient Greece, Rome, Byzantium, Persia, India, and other parts of the Islamic world. The caliphal library was not merely a place to hold books, but also an academy where scholars, scribes and translators gained and produced knowledge.

The library of Cordoba consisted of different sections, the most important of which, besides the writing section, was the translation section. A number of polyglot translators worked here, especially those mastering Latin, Greek, and Arabic. As such, translation thrived to new heights during Al-Hakam’s reign.

Baghdad, famously saw the birth of the ‘Translation movement’. Attached to the library was the translation bureau where famous scholars and eminent translators rendered books into Arabic. There were Hindu, Christian, Jewish and Parsi scholars who were paid handsome salaries. The House of Wisdom had in its treasures works on almost every subject and in every language. Harun al-Rashid would send envoys to various countries to procure books. Besides rare manuscripts in Arabic, he acquired manuscripts in Sanskrit, Zend-Avesta, Persian, Syriac and Coptic languages by paying top dollar for each book.

Unity, embracing diversity and working together for the greater good

By the 900s, drawing from a growing body of Greek, Persian, and Sanskrit works translated into Arabic, Islamic science quickly became the most sophisticated in the world. Christians, Jews, Hindus, and scholars from many other traditions, looked to Arabic as a language of science. Scientists of different faiths worked together, debating and studying with Arabic as the common tongue.

Al-Hakam II commissioned a joint committee to copy, translate, and write books comprised not only of Muslims but also Christians and Jews who worked in teams to preserve the human cultural, scientific, and intellectual legacy to be bequeathed to future generations. It was a time of peace where everyone were unified in their zeal for more knowledge.

The Arabs, Berbers, Jews, and Christians of medieval Cordoba gave stunning evidence that societies truly flourish when they embrace diversity and make room for difference, instead of seeing differences as a threat.

In the same way, in Baghdad, the famous translator Hunayn ibn Ishaq, was Christian; the mathematician Thabit ibn Qurra belonged to the Sabian religion; the Sindhi scientist Sind ibn Ali was born in what is now modern day Pakistan; the mathematician Al-Khwarizmi was from Persia; the Banu Musa brothers were from Persia; and Al-Kindi, who is considered today the father of Arab philosophy was from Iraq.

The idea of scholars from all walks of life working together to develop and discuss ideas was extremely central to Baghdad’s success. Working together in collaboration is a central pillar of advancing knowledge.

This mosaic of cultures and religions coexisting and living together in the House of Wisdom confirmed the idea that creativity never sprouts or blossoms in uniform climates. It is in our diversity that we are stronger. We all bring different skills, ideas and perspectives to the table.

Truly acting on the Quranic injunction to pursue knowledge

By far the biggest factor that stands out about these two magnificent periods, is in their mindset and intention. Their passion and drive wasn’t for the glory of their kingdom, or to spread the greatness of their family name. It was much, much deeper than that.

Much of this intellectual advancement can be traced to the precepts of the Qur’an. Throughout the Qur’an, there is a strong emphasis on the value of knowledge, because Muslims believe that Allah is all-knowing, they also believe that the human world’s quest for knowledge leads to further knowing of Allah. Muslims must thus pursue knowledge not only of God’s laws, but of the natural world as well, whilst extending the frontiers of human knowledge. The devout leadership of both these cities not only understood this well, they championed it.

Unlike the revealed knowledge of the Qur’an, Muslims believe that human knowledge is not perfect, and requires constant exploration and advancement through research and experimentation. According to the Qur’an, learning and gaining knowledge is the highest form of religious activity for Muslims, and the one which is most pleasing to God. They were simply acting out their purpose, their reason for being, doing what humans must strive for. It’s also why the Muslim world at this time were so far ahead of their counterparts in other areas of the world. Their world view was drenched in the lens of the Qu’ran. Since the pursuit of knowledge is viewed in a most positive light throughout the Qur’an, and understanding the Qu’ran helped them to understand their world, their experimentation and discovery was encouraged and indeed supported by the leadership, the scholars and the elite who shared that viewpoint. It was the Qur’anic world view that led the way. This worldview is in direct contrast to that which existed in the Europe of the Medieval Ages.

So advanced was Baghdad, according to the historian Ash-Shatti, that the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258AD where the rivers flowed black with the ink from all the books destroyed “set back the entire world scientifically, 500 years.”

Back in the modern day, what does this all mean for us?

So, how is any of this relevant to the reader? I don’t expect many statesmen or leaders of countries to read this. So what’s the point?

There are a lot of lessons we can learn, for our own business, organisations or even community, if you want to make an impact.

“Businesses owned by responsible and organized merchants will eventually surpass those owned by wealthy rulers.” — Ibn Khaldun

Looking at Ibn Khaludun’s quote, this we can definitely see playing out today. It is huge corporate conglomerates that rule the world. The famous FAANG (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google) revenues alone are more than the GDP of most countries. And they’ve done so, by echoing the zeal for knowledge that was displayed in Baghdad and Cordoba.

Peter Drucker, a world-renowned management consultant famously said:

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

With this oft-quoted statement, he was essentially saying that the culture within an organisation is much more powerful than even the best strategy in terms of long term, sustainable success. The dominant culture is often what people default to.

Many of the most successful companies today have a lifelong learning culture within their business that really sets them apart from most. Millennials now comprise the largest segment of the workforce, and a recent study shows that they rank training and development as the number 1 most valuable benefit employers can provide.

The way they see it, is that they still have a startup mentality, and are disrupting the traditional big companies, and the only way they’ll win is by the highest standards and by ongoing learning.

Tesla’s zeal for greatness — from the very top

“If you have two boxers of equal ability and one’s much smaller, the big guy’s going to crush the little guy, obviously, So the little guy better have a heck of a lot more skill. That is why our standards are high … They’re high because if they’re not high, we will die.” — Elon Musk — CEO, Tesla

Tesla’s CEO, Elon Musk is widely celebrated today as a modern day polymath. He has set up wildly successful business in fields as diverse as fintech (PayPal), automotive (Tesla) and even aerospace (Space X). His zeal for learning stems from his childhood, where according to his brother, Musk would read through two books per day in various disciplines.

Google’s Culture of Learning and Innovation

Google have a training method called G2G (Googler-to-Googler) which 80% of their training is done through. The “g2g” learning program is created to offer first-hand knowledge in different fields, from employees to other employees. In their own words, what makes it so successful for them is that “it promotes a culture that values learning.”

Google acknowledges the employees’ right to learn. Second, it gives them an opportunity to grow with an on-the-job-training and allows them to give back to other employees by participating in the program. Thirdly, they understand in a fast-paced world, microlearning is the best way. So a lot of their training is done through bite-sized lessons, ‘nudges’ and a “Whisper course” which were created to make messages “stick.” They are an innovator in their training — and also very transparent, making all their key learnings available here.

Google are also renowned for having a culture of innovation. Their ‘8 Pillars’ of Innovation are gold and a huge reason why they continue to create world class products, day in, day out.

Apple’s Holistic Learning and Polymathy

Apple, on the other hand are notoriously secretive. They too, value learning and development but don’t share their methods and discourage their staff from sharing. Like you’d expect though, Apple’s training takes place in-house and year-round. They have full-time academic staff that design and deliver their courses, with employees able to sign up for courses tailored to their position and background on an exclusive internal website.

As their whole motto is ‘Think Different’ — there is something interesting in terms of how Apple encourages people to think and develop. A course on ‘Communicating at Apple’ used Picasso’s drawings of ‘The Bull’ — which demonstrate how something complex can be broken down into its essential, core components. A Steve-Jobs-inspired course named ‘The Best Things’ encourages “employees to surround themselves with the best things, like talented peers and high-quality materials.”

Companies such as Apple have successfully used a holistic approach when adapting their designs. Originally Apple’s products showed little resemblance to each other because each department worked separately with its own heads of design. By using a holistic approach, Apple looked at all their products as a whole and designed them to have an overall synthesis. This, in turn, powered their brand image. Customers now buy Apple products to own a piece of the brand, as well as the product itself.

In an age of AI and as we enter the fourth industrial revolution, understanding the power of interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches has never been more important. Steve Jobs was known to be a modern day polymath, similar to Elon Musk. Both of them bust the myth of being a ‘jack of all trades, master of none’.

What they’ve shown is by learning across multiple fields, it provides an information advantage (and therefore an innovation advantage) because most people focus on just one field. For example, if you’re in the tech industry and everyone else is just reading technology publications, but you also know a lot about quantum physics or economics, you have the ability to come up with ideas that almost no one else could.

Amazon’s Ongoing Investment in Learning and Development

Amazon are a great example of a company investing a huge amount in their training and development. In 2019, they announced they would spend $700 million to upskill 100,000 of their US employees by 2025. Jeff Bezos also stated that “we pre-pay 95 percent of tuition, fees, and textbooks (up to $12,000) for certificates and associate degrees in high-demand occupations.” As one article surmised — whilst Amazon’s salaries, especially for warehouse staff might on the low side, their intention is to invest heavily in training, to make staff better and make them happier through their own growth.

Microsoft’s unity and bringing people together

Microsoft launched Hackathon in 2014 to help drive a culture change where employees would take risks to improve the world for better, by participating in projects.

“One place for everyone to come together, experience creative and fast-paced collaboration, make a difference, and drive the culture forward.” — Hackathon by Microsoft

This was not just for techies or coders, it’s a platform for everyone and their skill set. The projects range from assessing broadband availability, to helping the visually impaired get around more easily and even something as random as ‘Designing for the Zombie Apocalypse’. These act as platforms for sharing knowledge and ideas, while giving people a different scenario to practice their skills in. 2017 welcomed 18,000 people across 400 cities and 75 countries.

Airbnb’s Open Mindedness and a willingness to learn from others.

Fireside Chats are one way that Airbnb shows its dedication to learning. These internal events bring in industry leaders who share their insights on a certain topic. Airbnb says, “From CEOs to musicians, these leaders always have something invaluable to teach us.”

In conclusion, what can the Ummah learn from this?

To close, what does all this mean for Muslims, today? What can we learn from two random cities from over 1000 years ago and also from the modern tech giants that we can apply to our own situation?

There are a few big takeaways for me.

The first, is that when knowledge is truly championed and sought with sincerity, it rewards the seeker with insight and intellect and the ability to make a huge impact on society.

It wasn’t that they thought big, had big ambitions and did whatever it took to get there. It was actually, they were sincere to the seeking of knowledge and continuous improvement. The abundant achievements were simply a byproduct of that hungry, inquisitive, curious mindset and culture.

The second, is what can be achieved when something productive and good is truly encouraged by society and status — and it is facilitated effectively. The effects can compound and leave a lasting legacy.

The third is the power of unity and diversity, when all focusing on a big goal, a greater good.

Most importantly, is to look at what we’re lacking today. In the Muslim world in particular, perhaps none of these areas are scored particularly well in. Do we really look to other people different from ourselves, when seeking out knowledge? Do we have a Qur’anic world view and a polymathic approach? Do we encourage women to get involved?

There’s actually a bigger picture to all of this.

People say ‘the Americans are the best in the world. They have an entrepreneurial mindset, are go-getters and get things done. They’re the most advanced nation, etc. Sure, that may anecdotally be true — but perhaps this is only actually because they are the dominant superpower of the last century. It’s nothing to do with American culture per se. Yes you can argue they are confident and they have a positive mindset but this is a byproduct of being privileged. It’s the same of any superpower, they dominate innovation, technology and education before they dominate the world. The British last century would have been who you’d say we need to become like. 1000 years ago, as you can see from the above you would say you need to go and work in Baghdad or Cordoba. In the same way you may say that we need to work for a Chinese company in the coming years if we want to understand how to innovate at scale.

Ray Dalio has done an excellent study on this where he looks at empires as cycles over the last 500 years. In it, he tracks various metrics over the course of an empires rise and fall. Before any civilisation becomes dominant, they rank highly in education initially, then an increase in innovation and technology before other factors kick in. The US in that regard, are actually dwindling and declining considerably now.

The current education system stems from the industrial age and was put in place in the 19th Century — and the British and American empires have benefitted hugely from a populace mass-educated in this way — intelligent enough to follow orders, not intelligent enough to challenge and question. But as you can see, have we ever seen or heard of a society as harmonious and productive as the likes of Cordoba or Baghdad in the past 200 years? We may have big achievements and advancements, but it certainly hasn’t been done with peace and a prosperous impact for all.

THAT’s why we do what we do at KNOW. We understand that in order to reach this ‘Second Golden Age’, that our mindset towards seeking knowledge is critical. We need to elevate our thinking. We need to undergo a paradigm shift and change our very culture. The work MUST begin now.

The first port of call however, is a call for unity. To work towards the greater good. It is interesting to note that it was scholars working together to broaden and extend the boundaries of human knowledge that first became an established concept during the Golden Age of Islam and took us to the greatest of heights.

With such radical open-mindedness where ideas could be nurtured and creativity would be fostered, without the need for defence, debate or battle, it is certainly not a coincidence why that era became known as our Golden Age.

Muslims referred to Spain as Al-Andalus. This word has several meanings, one of which is “to become green after a long summer or drought”. May we live to revive the spirit of Andalus once again, in every sense of the word, ameen!